The Price of U.S. Imports From China Keeps Falling

More on:

The way trade is to be taxed at the border may—or may not—be about to change radically. But rather than speculate on the nature of the new world, I wanted to highlight one feature of the old.

I sometimes hear that China is loosing trade competitiveness because of rising domestic costs. And thus Chinese manufacturing firms need to move out of their ancestral homeland, either to low cost manufacturers like Vietnam or even to advanced economies like the U.S., in order to remain competitive.

I do not see it in the data. At least not in aggregate -- the stories of individual sectors of course could differ. .

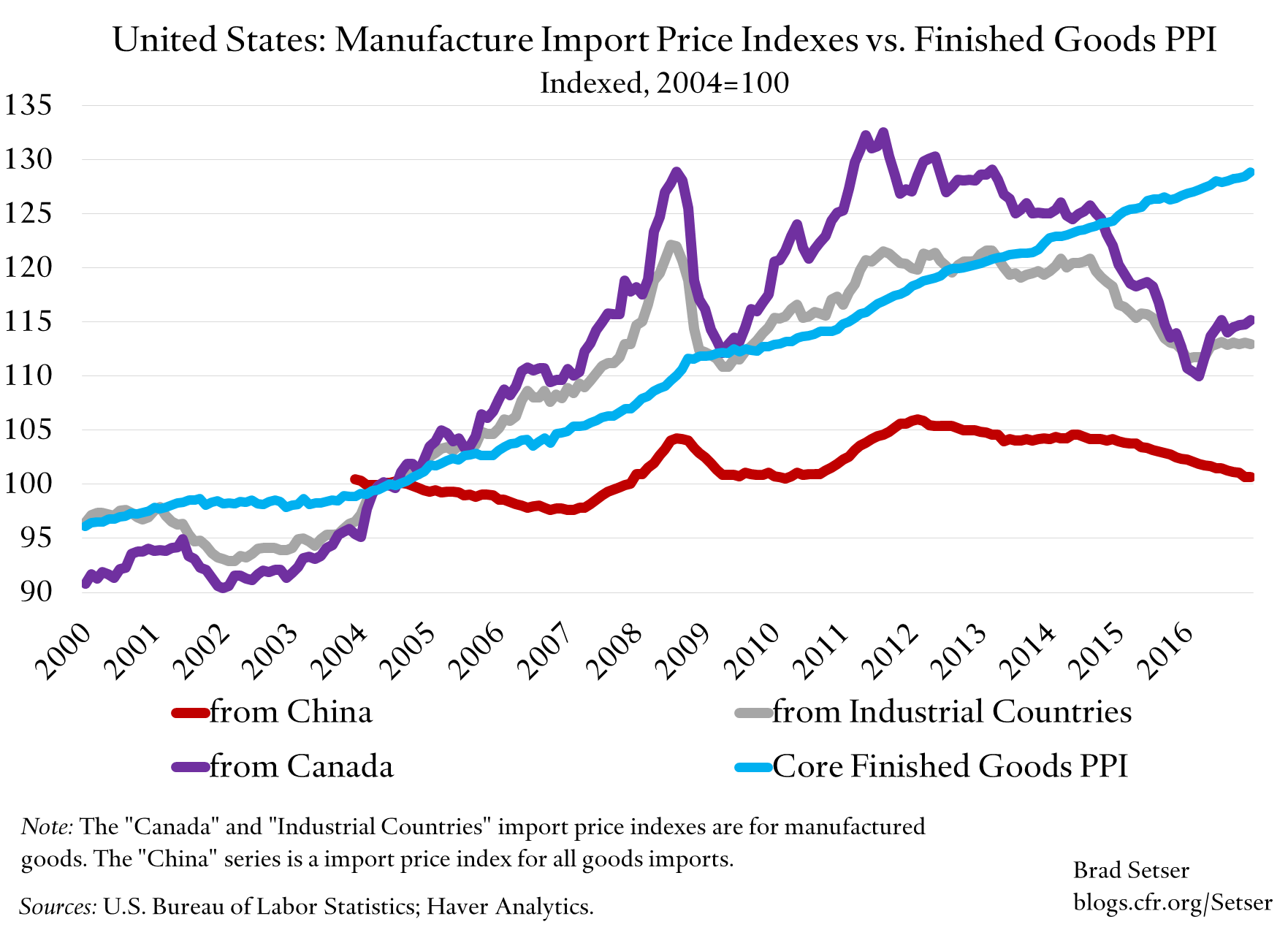

If the price of imports from China (as reported by the U.S. Department of Labor) is compared to the price of U.S. made finished goods and the price of domestic manufactures, Chinese goods not only look very competitive, but broadly speaking have been gaining in price competitiveness against U.S. made goods ever since the yuan stopped appreciating—and with the yuan depreciation of the past year, are poised to become even more competitive.

China maybe has lost a little of its previous edge over Canada and Europe thanks to the depreciation of the Canadian dollar and the euro over the past couple of years. But broadly speaking, the price of goods imported from China is back to where it was in 2004 (when the data series starts) while price of manufactured goods from the United States wealthier trading partners has gone up since then.

There is one potentially significant problem with the U.S. data here. About a quarter of U.S. imports from China are computers and cell phones. And getting the right "price" for goods marked by rapid technological change over time is hard. I suspect that the gap over time between the evolution of Chinese prices and U.S. finished goods prices would be smaller if computers and consumer electronics were removed. In fact, I would be thrilled if the BLS put out such a series. The area of real overlap between the U.S. and China increasingly is in the production of machined parts and capital goods (suggestions for how best to capture this most welcome, the right measure of U.S. prices might not be final goods excluding food and energy).

Setting that caveat aside though, I do not doubt that the basic story in the U.S. import price data is true: Over the past couple of years, the combination of U.S. workers and U.S. industrial robots has been loosing price competitiveness to the combination of Chinese workers and Chinese industrial robots.

And—building on points made by both Eichengreen and Krugman—it isn’t hard to see that the U.S. has gained in price competitiveness during periods of dollar weakness, and lost price competitiveness during periods of dollar strength. The data here is for import prices, but it reflects prices for all manufactures. 2007 was a very good year for U.S. exports for example. 2015 and 2016, by contrast, were not.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store